Although the advent of anti-VEGF therapy (also called eye injections, explained below) has revolutionized the treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD), there are still a number of persons – although in the minority – who do not respond to treatment. It is these “non-responders” or “reduced responders” who continue to pose significant challenges to doctors and researchers.

Since there are not, at present, specific protocols that govern ophthalmologists’ decisions to switch patients from one eye injection treatment to another, it can be difficult to determine when – or if – a treatment switch should occur. In order to address these persistent questions, a team of medical researchers has analyzed patient data collected during the groundbreaking Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (explained below). They concluded that some (but not all) persons with a poor initial response to eye injection drugs may still respond to treatment with the same drug over time without being switched to an alternative drug.

The study, entitled Association of Baseline Characteristics and Early Vision Response with 2-Year Vision Outcomes in the Comparison of AMD Treatments Trials (CATT), has been published online ahead-of-print in the September 14, 2015 edition of Ophthalmology, the official journal of the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology publishes original, peer-reviewed research in ophthalmology, including new diagnostic and surgical techniques, the latest drug findings, and results of clinical trials.

The authors are Gui-shuang Ying; Maureen G. Maguire; Ebenezer Daniel; Frederick L. Ferris; Glenn J. Jaffe; Juan E. Grunwald; Cynthia A. Toth; Jiayan Huang; and Daniel F. Martin, on behalf of the Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) Research Group. The authors represent the following institutions: the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; Duke University, Durham, North Carolina; and Cole Eye Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio.

Some Background on the Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT)

The Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) was a groundbreaking multi-center, prospective clinical trial that evaluated the effectiveness of Avastin (bevacizumab) versus Lucentis (ranibizumab) in a head-to-head study. CATT was funded by the National Eye Institute (NEI), a component agency of the National Institutes of Health.

You can read more about the history of CATT at Review of Ophthalmology and at Avastin vs. Lucentis for AMD: Preliminary Research Results, Avastin and Lucentis for Macular Degeneration: Head-to-Head Once Again, and Which Real-Life Factors Influence Adherence to Lucentis Treatment for Macular Degeneration? on the VisionAware blog.

About Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

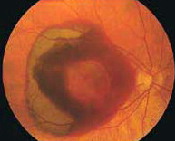

In wet macular degeneration, the choroid (a part of the eye containing blood vessels that nourish the retina) begins to sprout abnormal blood vessels that develop into a cluster under the macula, called choroidal neovascularization (neo = new; vascular = blood vessels).

The macula is the part of the retina that provides the clearest central vision. Because these new blood vessels are abnormal, they tend to break, bleed, and leak fluid under the macula, causing it to lift up and pull away from its base. This damages the fragile photoreceptor cells, which sense and receive light, resulting in a rapid and severe loss of central vision.

Anti-Angiogenic Drugs

Angiogenesis is a term used to describe the growth of new blood vessels and plays a crucial role in the normal development of body organs and tissue. Sometimes, however, excessive and abnormal blood vessel development can occur in diseases such as cancer (tumor growth) and AMD (retinal and macular bleeding).

Substances that stop the growth of these excessive blood vessels are called anti-angiogenic (anti=against; angio=vessel; genic=development), and anti-neovascular (anti=against; neo=new; vascular=blood vessels).

The focus of current anti-angiogenic drug treatments for wet AMD is to reduce the level of a particular protein (vascular endothelial growth factor, or VEGF) that stimulates abnormal blood vessel growth in the retina and macula; thus, these drugs are classified as anti-VEGF treatments. At present, these drugs are administered by injection directly into the eye after the surface has been numbed.

Avastin

Avastin is an anti-VEGF drug that is FDA-approved since 2004 for intravenous use in colorectal cancer. It is currently used on an “off-label” basis (i.e., via eye injection) to treat wet AMD. The cost per treatment with Avastin is approximately $50.

Lucentis

Lucentis was derived from a protein similar to Avastin, specifically for injection in the eye to block blood vessel growth in AMD. In 2005, clinical trials established Lucentis as highly effective for the treatment of wet AMD. The FDA approved Lucentis in 2006. The cost per treatment with Lucentis is approximately $1,200-$2,000.

Eylea

Eylea was approved by the FDA in late 2011 as an effective treatment for wet AMD. It is administered once every two months after three initial once-a-month injections.

Please note: The CATT study involved only Avastin and Lucentis. It tested monthly dosing, used in Lucentis trials, and dosing “as needed” (called “pro re nata,” or PRN), used in Avastin treatment for AMD.

About the Non-Responder Research

Excerpted/Adapted from AMD: Continued Anti-VEGF Treatment May Induce Response from Medscape Multispecialty (registration required):

“To date, there are no widely accepted criteria for switching anti-VEGF drugs,” the study investigators note. For this study that analyzed data from CATT, they devised their own criteria for when patients were hypothetically eligible to switch medications.

- First, patients had to have a visual acuity of 20/40 or worse.

- Second, patients had to have gains of less than one line of vision (as measured by an eye chart) in response to their initial VEGF therapy, at either 12 or 24 weeks.

- Third, patients had to have persistent fluid at the center of the fovea [located in the center of the macula, providing the sharpest detail vision] on optical coherence tomography [high-resolution imaging of the inside of the eye].

- Last, patients had to have received all three initial monthly treatments of either anti-VEGF agent up to the time of the hypothetical switch point for switching at week 12, and to have received five of six monthly treatments to be hypothetically switched at week 24.

Dr. Ying and colleagues note that it was “surprising” to learn that the visual acuity response at 12 weeks predicted less than 50% of the variation in visual acuity responses at both years 1 and 2. “This fluctuation of visual acuity during the course of anti-VEGF treatment makes it challenging to determine the beneficial effect on visual acuity from switching to another treatment,” the investigators write.

For example, eyes that had a visual acuity gain of at least one line at 12 weeks generally had a similar gain at years 1 and 2. However, 17% of eyes that initially showed a loss of one line or more [at 12 weeks] gained one line or more at year 1, as did 27% of eyes by year 2.

“This shift from early visual acuity loss to later visual acuity gain contributes to the lower than expected association between early visual acuity response and later visual acuity response at years 1 or 2,” the authors write.

“In addition, the fact that a meaningful percentage of eyes eventually had visual acuity gain despite early loss is encouraging and should prompt ophthalmologists and patients not to give up anti-VEGF treatment, even if early visual acuity response is not optimal.”

“I think one of the key findings from this study is that if a patient responds to anti-VEGF treatment after the first three injections — in other words, by week 12 — they will most likely continue to respond with further treatment, and treatment should continue,” [said study author Gui-shuang Ying, PhD].

“On the other hand, if a patient does not respond well by week 12, they should still be given an opportunity to continue with treatment, as they have a reasonably good opportunity to gain visual acuity by year 2 with continued treatment, using the same drug.”

Given that there are no guidelines governing the way ophthalmologists should switch patients from one anti-VEGF treatment to another, [study author] Dr. Ying called for a randomized controlled trial to compare patients who do not appear to be responding well on one anti-VEGF agent and who are switched to a new agent with similar patients who continue receiving the same treatment to see whether switching really does improve visual acuity.

More about the Research from Ophthalmology

From the article abstract:

Purpose: To evaluate the association of baseline characteristics and early visual acuity (VA) response with visual outcomes at years 1 or 2 in the Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) Treatments Trials (CATT).

Design: Secondary analysis of CATT

Participants: The 1185 CATT participants with baseline VA of 20/25 to 20/320

Methods: Participants were assigned to [Lucentis] or [Avastin] and to 1 of 3 dosing regimens. Associations of baseline characteristics and early VA response (week 4 or 12) with VA response at years 1 or 2 were assessed. Patients who had a poor initial response (visual acuity 20/40 or worse with persistent fluid and without [at least a 1-line visual acuity gain] were defined as candidates for changing treatment.

Results: Baseline predictors for less visual acuity gain at year 2 were older age, visual acuity of 20/40 or better, larger choroidal neovascularization area, presence of geographic atrophy, total foveal thickness [less than 325 micrometers or greater than 425 micrometers], and elevation of retinal pigment epithelium.

Conclusions: Visual acuity response at week 12 is more predictive of 2-year vision outcomes than either several baseline characteristics or week 4 response. Eyes with poor initial response may benefit from continued treatment without switching to another drug.