Although the injectable drugs Lucentis, Eylea, or Avastin have revolutionized the treatment of wet macular degeneration and diabetic eye disease, questions persist among persons with these eye disorders about the safety and tolerability of the eye injection procedures themselves: “How painful are they?” and “Are they safe? What are the chances that I’ll get a serious eye infection?”

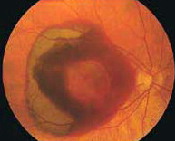

Of particular concern to doctors and patients alike is the possibility of post-operative, post-injection endophthalmitis, an inflammation of the internal parts of the eye that can be an extremely serious complication of intraocular [i.e., within the eye] surgery.

Now, a new study designed to answer doctors’ questions about (a) the rates of post-injection endophthalmitis and (b) the most effective protocols to prevent endophthalmitis has also yielded information that may provide some reassurance to patients who are undergoing injection treatments for eye disease.

Short answer: The rate of post-injection endophthalmitis is extremely low. In this particular study, only 30 cases of endophthalmitis occurred after 90,339 eye injections. The researchers also confirmed for doctors that the use of antibiotic eye drops prior to the eye injection had minimal effect on the rate of post-injection infections.

About the Research from Retina

This new research, entitled Endophthalmitis after Intravitreal Injection: the Role of Prophylactic Topical Ophthalmic Antibiotics (explained below), has been published in the July 2016 edition of Retina: The Journal of Retinal and Vitreous Diseases. Retina is a peer-reviewed journal, published monthly, that focuses exclusively on retinal disorders and provides current information on diagnostic and therapeutic techniques.

The authors are Alexa L. Li; Charles C. Wykoff, MD, PhD; Rui Wang; Eric Chen, MD; Matthew S. Benz, MD; Richard H. Fish, MD; Tien P. Wong, MD; James C. Major Jr., MD, PhD; David M. Brown, MD; Amy C. Schefler, MD; Rosa Y. Kim, MD; and Ronan E. O’Malley, MD, from Retina Consultants of Houston, Blanton Eye Institute, and Houston Methodist Hospital, all from Houston, Texas.

What Is Endophthalmitis?

Endophthalmitis is an inflammation of the internal parts of the eye that is a possible complication of all intra-ocular [i.e., within the eye] treatments and surgeries, but particularly cataract surgery. Post-operative endophthalmitis is a rare, extremely serious complication of intraocular surgery.

Endophthalmitis is usually the result of a bacterial infection. The most common bacteria found to cause this infection are the “staph” (staphylococcus) and “strep” (streptococcal) bacteria, which normally live on human skin. Endophthalmitis usually develops in the first week after surgery and causes a range of symptoms, including pain, redness, decreasing vision, eyelid redness or swelling, or a yellow/green discharge from the eye.

Should any of these symptoms develop, it is extremely important to seek medical care immediately. The sooner endophthalmitis is treated, the better the prognosis for the eye and vision. Endophthalmitis is treated either with antibiotics injected into the eye or with surgery plus antibiotics injected into the eye. Even with treatment, the vision and the eye can be permanently damaged.

About Wet Macular Degeneration, Diabetic Eye Disease, and Eye Injections

In wet macular degeneration and diabetic eye disease, abnormal blood vessels develop that can break, bleed, and leak fluid. If left untreated, these damaged blood vessels can result in a rapid and severe loss of vision. The most effective treatments to date for this blood vessel damage are the injectable drugs Lucentis, Eylea, or Avastin.

At present, these drugs are administered by injection with a very small needle directly into the eye after the surface has been numbed. This is called an “intra-vitreal” injection because the doctor injects the needle directly into the vitreous gel that fills the inside of the eye and gives the eye its shape.

The needle is very small and is inserted near the corner of the eye – not the center. During the injection procedure, the doctor will ask the patient to look in the opposite direction to expose the injection site, which also allows the patient to avoid seeing the needle.

About the Research

Excerpted from Endophthalmitis Risk Low after Intravitreal Injection at Medscape (registration required):

Intravitreal injections are a common treatment for retinal pathologies, including [wet] age-related macular degeneration, diabetic [eye disease], and retinal vein occlusion. Patients usually tolerate these procedures well, but can develop a rare but potentially disastrous infection known as endophthalmitis.

In the past, many physicians have prescribed topical antibiotics in the peri-intravitreal injection period [i.e., the time immediately before, or prior to, the eye injection], but this practice has fallen out of favor; 90.5% of 2015 respondents to the Preferences and Trends survey reported that they do not use antibiotics with these injections.

In the current study, the authors retrospectively [i.e., using past records] identified patients who underwent intravitreal injections at all offices of a large retina-only practice from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2014.

[The doctors] used prophylactic antibiotics from January 1, 2011, through December 2011 and did not use them from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2014. The doctors phased out use of the antibiotics during 2012, and the researchers considered this year to be the transition period. [Editor’s note: “Prophylactic” describes a medicine or course of action used to prevent disease or the spread or occurrence of disease or infection.]

A total of 30 cases of clinically suspected endophthalmitis occurred post-injection and were treated, for a rate of 0.033%, or about one case for every 3,011 intravitreal injections. Per year, the number of identified and treated endophthalmitis cases was six in 2011, 13 in 2012, seven in 2013, and four in 2014.

“Owing to the nature of performing intravitreal injections, there is a risk of contamination with nasopharyngeal [i.e., affecting the nose and the pharynx, which is the tube connecting the mouth and nasal passages with the esophagus] micro-organisms, including streptococcal organisms. Masks were not a part of the standard protocol in the current series,” the authors write. “Most retina specialists recommend either wearing a surgical mask or minimizing talking while preparing and administering intravitreal injections.”

Endophthalmitis rates did not differ significantly during the period in which patients received prophylactic antibiotics (6 out of 16,984, or 0.035%) compared with the period in which patients did not receive prophylactic antibiotics (11 out 53,345, or 0.021%). Of the patients who developed endophthalmitis, 12 (40%) had diabetes mellitus.

More about the Study from Retina

Edited and excerpted from the study abstract:

Purpose: To determine the rate of post-intravitreal injection endophthalmitis and to assess microbiological features and outcomes with and without the use of peri-intravitreal injection topical ophthalmic antibiotics.

Methods: Consecutive series of endophthalmitis cases retrospectively identified after intravitreal injection at a multicenter, retina-only referral practice (Retina Consultants of Houston) from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2014. Prophylactic peri-intravitreal injection topical antibiotics were routinely used during the initial 12-month period (January 1, 2011–December 31, 2011) and not used in the final 24-month period (January 1, 2013–December 31, 2014). Main outcome measures were incidence of endophthalmitis, microbiology results, treatment strategies, and visual outcomes.

Results: Of 90,339 intravitreal injections, 30 cases of endophthalmitis were identified (endophthalmitis rate = 0.033%; or approximately 1 of 3,011 intravitreal injections). The most common organisms isolated were coagulase-negative staphylococci (n = 10, 33%), followed by Streptococcus mitis (n = 2, 7%). Fourteen cases (47%) were culture negative. Peri-intravitreal injection topical antibiotic prophylaxis did not decrease the rate of endophthalmitis (0.035%) with antibiotic use versus 0.021% without antibiotic use.

Conclusion: The risk of endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection remains low, with coagulase-negative staphylococci and Streptococcus mitis the most common bacterial isolates identified. Prophylactic peri-intravitreal injection topical ophthalmic antibiotic use did not decrease the endophthalmitis rate.

Additional Information

- New Research Indicates Long-Term Positive Effects of Intensive Blood Sugar Control on the Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy

- New Macular Degeneration Research from the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study

- Researchers Identify a Mechanism that May Explain Why Some People Experience Accelerated Diabetic Retinopathy and Vision Loss